“I Invest in the Internet”

There are no longer “internet funds”. We don’t invest in the “internet” anymore. .coms are not the destination but part of a broader internet protocol that underpins communications. Crypto will be similar. “Crypto funds” will soon be just funds. And crypto itself will be the invisible backbone of digital markets.

Crypto will grow. It will slowly hook into everything we do. But as investors, our guiding question is not “will crypto grow?” but rather “is crypto a good investment”?

Fat vs. Thin Protocols

Ethereum has long served as an indexed bet on crypto innovation. It is the first and most established smart contract platform and has disproportionately accrued capital, users, and developers. As applications and users have grown, so has Ether’s price. Ethereum appears to soak up the value of the activity that lives upon it.

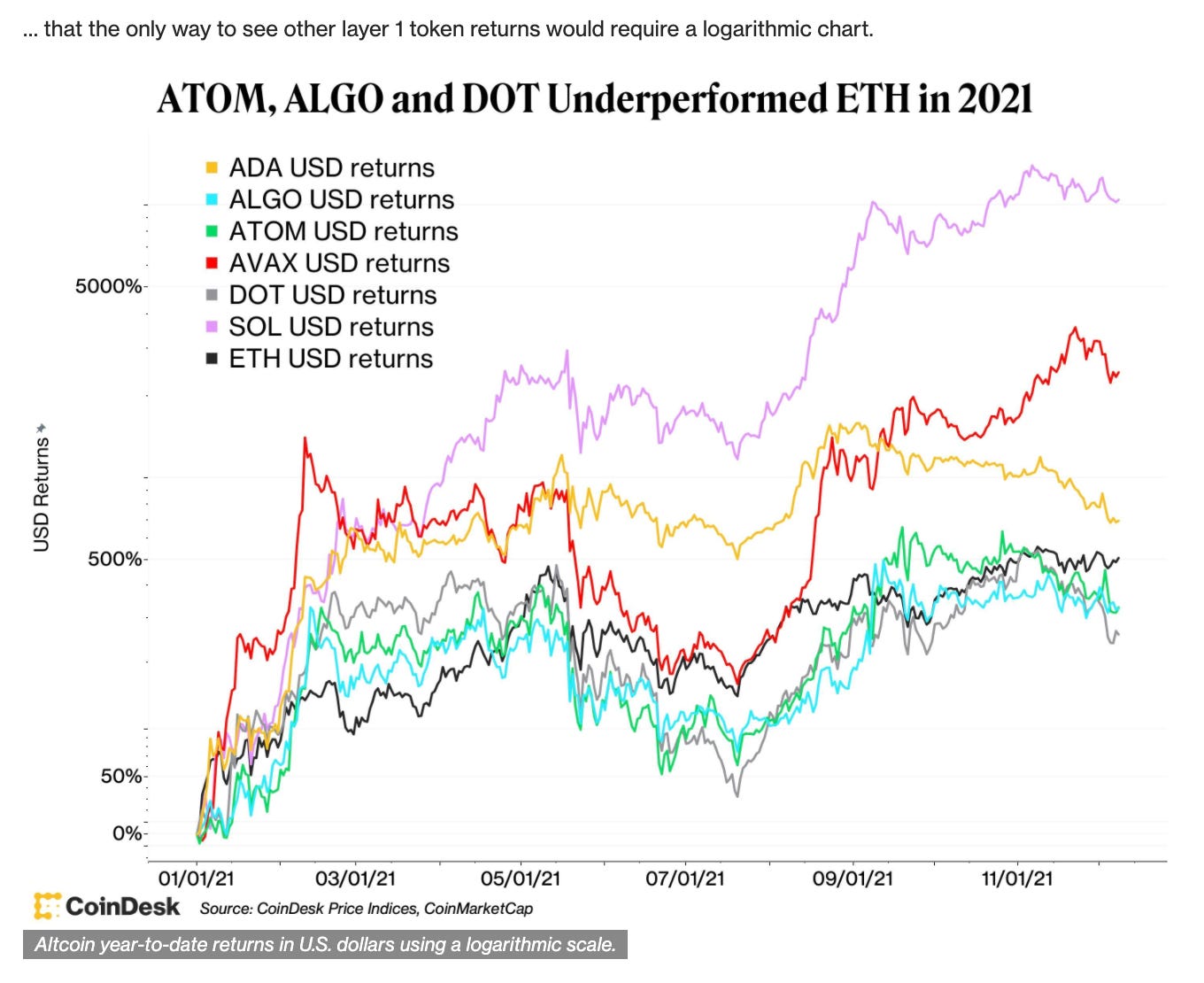

One of the most lucrative investment strategies of 2021 was to rotate between alternative Layer 1 blockchains. Savvy traders started the year with Solana, grabbed Avalanche, Luna, Fantom, then Near, and so on. Ethereum is too expensive for average retail users to transact on, so more accessible Layer 1s have popped up to fill the void.

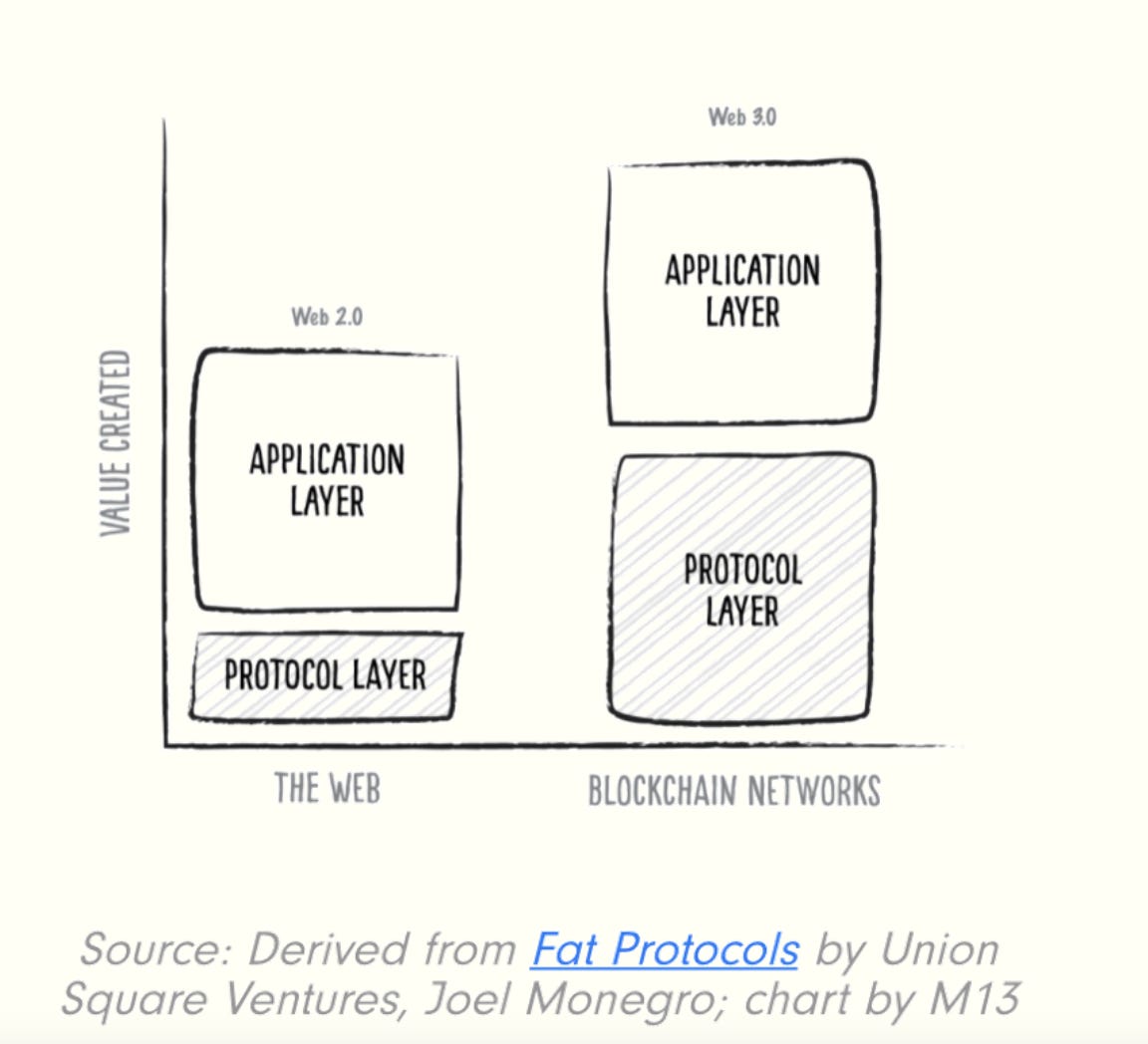

Layer 1s are designed similarly—in order to transact, a user must spend the native L1 token, be it Ether, Solana, or any of the others. And because non-Ethereum L1s are more accessible and can host a wider array of new applications, the potential TAM of such protocols are much larger. Investors recognize the opportunity to invest directionally at the base of a thriving young ecosystem. These L1 bets are based on the premise that the deepest part of the stack will soak up the value that lives upon it. This dynamic is called the “fat protocol thesis”.

The alternative to a fat protocol is a thin one. This is a set of rules that fades into the background and fails to accrue value. Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and the Internet Protocol (IP), collectively the Internet protocol suite, are ubiquitous yet brutally thin. Despite being the progenitor of internet commerce, TCP/IP is un-investable.

Growth is not Always Investable

An accretive investment is a stake, priced properly, in a store of value or a business (productive asset). A good store of value (SoV) serves as a Schelling point for savers and investors. SoVs often fail to generate earnings. Examples include gold and Burgundy wine. A good business must ultimately generate earnings. And a good investment should ultimately have rights to those earnings. Examples include single-family homes, a SaaS business, Kraft Heinz stock, or an emerging markets REIT.

Layer 1 blockchains are the pipes of crypto. Investors regard Layer 1s as indexed, infrastructural bets on emerging ecosystems with large total addressable markets (TAMs). Instead of fretting about which applications at the top of the stack will accrue value, they’ll invest at the bottom, where value trickles down. You can bet directionally instead of idiosyncratically.

The more I reflect on this logic, the less defensible it seems. Crypto is too young for there to be obvious indexed bets. Even Ethereum is ultimately a start-up in a fiercely competitive and unpredictable ecosystem. Beta is a product of maturity. Instead of evaluating crypto in a vacuum, we should look to history for guidance on how infrastructure has interacted with growth industries. This will cast light on if and how Layer 1 native tokens will accrue value and act as sound investments.

Picks and Shovels: .com

During the internet boom, it was of course chic to bet not on individual .coms, but on enabling technologies. Hardened fund managers were too sage to make targeted bets in such a dynamic, adversarial environment. Instead of prospecting for gold, they bought “picks and shovels”.

The computing stack, Source

For the internet to realize its promise, it would need a supply of networking or communications infrastructure. This meant expansion of bandwidth and deployment of optical fiber. Telecoms like Deutsche Telekom and Cisco and optical fiber companies like Ciena and Corvis, bootstrapping the networking layer, were darlings of the era. The investment logic went as follows: just collect equity in a few of these “fat protocols” and coast accretively upon the wave of technological acceleration. You “were derided if you claimed that telecoms were poor investments or bad businesses”. (John Pfeffer)

As it turns out, telecoms were terrible businesses. They were capital intensive, commoditized, and vulnerable to frequent Schumpeterian destruction. Because the feedback loops for the construction of physical infrastructure were so delayed, telecoms were prone to overbuilding and thus cyclicality. It was a race to the bottom: communications infrastructure providers battled to see who could provide the most processing for the cheapest price. Twenty years later, Deutsche Telekom and Cisco remain below their internet bubble highs.

As it turns out, it was the application layer rather than the networking layer that captured value. Networks like eBay, Amazon*, and Google built network effects, moats, and pricing power. We are now reimagining the internet because the application layer got too fat. With this imagination comes a youthful conviction in the fatness of the networking layer.

*Amazon is an interesting case where it succeeded initially by creating an application/aggregator that lived on internet rails. Only later did one of Bezos’ experiments, AWS, become successful server infrastructure. What I find particularly interesting about AWS is that it represents “picks and shovels” for businesses, not users. Users expect free.

Photo Credit: Smithsonian Art Museum

Picks and Shovels Redux: .eth, .sol, .ust

Ethereum set out to be a global supercomputer for users to enjoy without risk of censorship or need for permission. Instead of serving as the open backbone of the new internet, it has become overburdened with traffic and is prohibitively expensive to transact on. Because blockspace, or processing, is fixed, demand drives up the cost of access. Ethereum has become a victim of its own success.

The network might have responded by adjusting the block size to offset the increase in demand. Instead, Ethereum has pushed for a change to the monetary policy via Ethereum Improvement Proposal 1559. This proposal introduces a deflationary mechanism to the money supply—it burns all transaction fees, denominated in Ethereum, from existence. Instead of pushing for abundance and accessibility, Ethereum is pushing for scarcity and exclusivity.** It is converging on hard money.

** To be very fair, sharding intends to address scalability and storage.

To me, there is a catch-22 in Layer 1 blockchain land. To be an accessible supercomputer for the masses, you need a high-throughput, low cost blockchain that does not extract rents from its users. But for a Layer 1 token to be valuable as “equity” in a business, that Layer 1 blockchain must capture rent from users.

As Ethereum mimics Bitcoin with EIP 1559, alternative Layer 1s like Solana enter the fray with more abundant blockspace and cheaper fees for users. Surely Solana can learn from what Ethereum botched and onboard billions via high throughput and a robust crop of applications that the low cost environment permits. Sadly the Solana network has been down frequently towards the end of 2021 and early 2022. These outages were caused by actors spamming the network and clogging the pipes. Because transactions are cheap, there is very little cost to such bombardment. Anatoly Yakavenko has suggested that the protocol will have to introduce a “fee market” which will create preferential access conditions and relieve the network.

Source: CBS Austin

The introduction of higher tolls, whether by stake-weighted access or other mechanisms, will make spamming more expensive and reduce traffic. So let’s synthesize: a network that sought to be the accessible alternative to the once accessible supercomputer (Ethereum) is now pushing towards value capture. It seems we may have happened upon a pattern.

For a Layer 1 blockchain to become a good business, it must start capturing rents from its users. As soon as a protocol is perceived as overly extractive, an alternative L1 will pop-up to service dissatisfied users. We can look to the rise of Binance Smart Chain, Avalanche, and Solana as evidence of this dynamic.

A Layer 1 blockchain can be either fat and non-accessible or thin and ultra-accessible. On the fat side, native L1 assets move toward hard money. On the thin side, it is a race to the bottom: who can provide the most processing for the cheapest price? This is starting to sound familiar.

Buffetting a Blockchain

As an investor, I am less interested in finding the next hard money/unproductive store of value than I am in finding and owning great businesses. In many ways, the non-productive stores of value that people choose are arbitrary and subject to the whims of humanity. Gold certainly has properties that make it a suitable schelling point for wealth preservation: it’s scarce, dense, and difficult to counterfeit. But obsidian, diamond, silver, and platinum could all work as well.

If your “business” is that of being hard money, I think Bitcoin beats you in most simulations. If, in the limit, L1 “computing” assets like Ether and Solana converge on Bitcoin’s core value proposition, hard money, I will own much less of them than if they were represented ownership in strong, cash-flowing businesses with defensible moats.

John Pfeffer, from whom I borrowed many of the ideas in this piece, suggests that a good business has seven components: A) Growth, B) Sustainable (high) barriers to entry C) Not in a highly fragmented market D) Not exposed to frequent technological disruption E) Healthy margins F) Not capital intensive G) Maintains pricing power

Pricing power is the single most important decision when evaluating a business. - Warren Buffett

How do Layer 1 blockchains fit into this matrix? Growth: Layer 1 blockchains have grown rapidly in terms of transaction volume, total value locked, active developers, daily active wallets etc. Barriers to Entry: Software is open-source and can be forked easily. Capital is abundant so ecosystem growth can be easily incentivized. Barriers are low. Fragmentation: Though somewhat concentrated, there are over 50 smart contract Layer 1s. The space is competitive. Disruption: The industry is subject to constant changes to consensus mechanisms, block size, and other parameters. Margins: Difficult to reason about this one. Unlike a company, a protocol does not generate revenue for its treasury. The fees of the network go to those securing that network, usually miners or validators. In theory, users and developers should pay high fees for security. Capital Intensive: Virtually no capital outlays. Minimal physical footprint and zero marginal cost to the production of software. Pricing Power: Pricing power is a function of barriers to entry. If barriers to entry are low, pricing power is low. Thus, Layer 1 blockchain pricing power is low.

So the obvious logical extreme here is: what makes a Layer 1 blockchain resilient to forking or any other type of disruption? Can a fat, extractive Layer 1 really maintain a moat over the long-term? I am not sure. To visualize, let’s pivot to a prosaic analogy.

Fat Government Thesis: A Real-World Analogy for the Fat Protocol Thesis

City residents are customers of a government. The government sells services like education, transport, safety, and sanitation and in return receive payment, or taxes. The residents weigh the cost of doing business (gas) against the quality of life they are entitled to. If the government protocol becomes overly extractive, too fat, the city’s customers will leave.

Web3 users will exercise similar logic. Each Layer 1 ecosystem hosts applications which collectively convey a user’s “quality of life”. As long as gas fees (taxes) are reasonable vis a vis the utility of the applications, users will remain. If the protocol gets too fat, they’ll leave. Switching costs between blockchains are much lower than switching costs between cities. Cities are also less fungible—beauty cannot be forked.

It seems that extraction at the protocol level has an upper bound. And just like in Web2: while most lower-level protocols will not be good investments, other parts of the stack will be.

So where are the good businesses?

The most important thing [is] trying to find a business with a wide and long-lasting moat around it … protecting a terrific economic castle with an honest lord in charge of the castle. - Warren Buffett

A good business is one with a moat. Whether at the protocol layer or the application layer, sustainable, superior protocols will grow market share and capture value. Of course, such crypto businesses will benefit from different structural and strategic advantages than their industrial or even Web2 counterparts. IP, production efficiency, access to physical resources, and regulatory barriers are largely irrelevant to crypto.

In the world of open-source software, the moat lies in how difficult it is to “fork” value. If the code or product is copied, what premium remains for investors? In my view, the moats of crypto-businesses are distributed across the following:

Brand: Brand is a proxy for reputation which is a proxy for trust. Trust takes years to build and seconds to destroy. In an industry so young, a strong brand is even rarer and thus even more powerful. A powerful brand is ultimately what allows companies like Apple and Goldman Sachs to drive pricing power and continue to capture value.

Security: Onboarding users/institutions into crypto is hard enough. Users must grow comfortable with facing software, rather than a human counterparty to whom they may have recourse. Protocols with a long, unblemished history of ingesting, holding and returning user funds safely have an obvious edge.

Community: The tribe around a protocol drives organic marketing, delivers highly targeted product feedback, and carries the torch through good times and bad. When COVID forced restaurants to shutter eat-in business, it was those with loyal patrons who prevailed in a take-out only world. When a protocol hits turbulence, the product is struggling, and the token is down, a community can keep it from fizzling.

Team: Because crypto is open-source and hyper-adversarial, protocols with core teams that ship fast and ship well are at an advantage. Tesla isn’t winning because it built good tech and established an IP moat. It’s winning because it has consistently built excellent products and user experiences for a decade. In a Red Queen environment like crypto, a protocol must run faster than its competitors to gain any ground.

Integrations: Just like in traditional business, partnerships are sticky and difficult to replicate. These relationships take time to build and are mutually beneficial.

Network Effects: A strong network drives utility for the user and increases the opportunity cost of doing business elsewhere. Take Ethereum: many nodes run the protocol, so it has high security guarantees. Because of the high security guarantees, lots of value lives on Ethereum, which drives more nodes to secure the network, and so on. Ultimately, because a network effect feeds on itself in a runaway manner, it is very difficult to replicate.

Pricing Power: Pricing power is the sum effect of the previous dimensions. A moat is only useful if there is current or future revenue to grow and defend.

A battle-tested, reputable protocol with a passionate community and capable team that has forged integrations across other protocols and cultivated a powerful network effect is on its way to securing a moat. For the purposes of demonstration only, see the following chart of various applications measured along each moat dimension (1-5) for a total scoring out of 35:

History Doesn’t Repeat Itself, But it Often Rhymes

Each successive technological revolution is unique. The dynamics of the industrial revolution were different than those of the internet revolution which will be different than those of the blockchain revolution. But driving each paradigm were effectively the same humans. Human nature barely changes, so history rhymes. To claim that “this time is different” is always fair game. But to me the burden of proof is on the person who prophesies a deviation from the historical rhythm.

Irrespective of the era, technological waves evolve in similar ways. Smart people recognize an opportunity to expand into the frontier. On the frontier is an abundance of uncertainty and thus opportunity. As people and companies compete, that frontier ossifies, gets commoditized away, and is relegated to a lower part of the technological stack. The new frontier then moves higher in the stack.

The agricultural revolution commoditized food production. The industrial revolution commoditized manufacturing. The internet revolution commoditized communications. The blockchain revolution will commoditize transactions.

Similarly to the Web2 era, most infrastructural protocols in Web3 will not accrue value. As I plunge deeper into these dynamics, I am beginning to see the vague outline of an exception. A very specific infrastructural variant, which of course has an analog in Web2, may capture value. (I will likely discuss this in a future piece). But for the most part, the application layer will once again reign supreme. Good businesses usually lives higher in the stack.

Note: Thank you to Joe Hosler and Michael Even for providing guidance and enduring my insufferable ranting.

Sources: Dot.Con: How America Lost Its Mind and Money in the Internet Era, Invest Like the Best: John Pfeffer

Disclaimer: TJ Ragsdale and Lupine Capital I, LP may own some of the tokens mentioned. TJ Ragsdale contributes to MakerDAO. This piece is intended purely for educational purposes and is in no way, shape, or form financial advice.

Great read! Love the way you approach it. I think there's a lot more to be said about where in the stack Web3 protocols actually exist in the first place. The fat protocol government analogy is great but leaves a lot of wiggle room in the details. Pretty sure you're going to start dialing into this in your next posts so looking forward to that.

The only thing I'd quibble about is the business model for open-source. I think the evidence points to long-term service-models (integration, maintainence, operations, etc.) as the primary source of business revenue in open-source software. Where you mention integrations and community captures some of that, but not in it's entirety. In relation to crypto, the emphasis on decentralization has off-loaded a lot of this work, but I think that's only temporary. In the long-run, those who can figure out the maintainence model of a protocol and it's associated ecosystem is where my guess is - whether they're a DAO or not.

Really well written. Subscribed!

Great piece. Brand is an underrated factor in evaluating the stability of crypto protocols. Users and investors in crypto are notoriously fickle, their attention span is generally short and most are constantly moving between protocols and apeing into the next 'hot' thing. Creating a brand which is seen as reliable, long-term and resistant to FUD is a super power for blockchains or protocols. BTC, ETH, MKR etc all doing it successfully. Alt L1s and DeFi 2.0 (Olympus etc) still have a long way to go to build trusted brands.